On my adventure trip I had brought many gadgets with me on the road and on the mountains – see also my pre-departure post ‘Got Gadgets?‘. My goal was to remain fairly well connected (email, skype, phone, etc.) throughout my trip and also to enrich my experience during and after the trip (via music, photos, GPS tracker etc.). This has resulted in a much richer and more instant documentation of the trip than would have been possible say 20 years ago.

I was rarely more than a few hours away from the nearest Internet connection, and using my iPhone for taking daily notes as well as my little Netbook for email and updating my Blog had become second nature for me. The technology worked well, as I expected. One less expected aspect was my capacity and interest to engage, which was often muted. I had thought I would use my Spanish learning apps, my games and puzzle apps, or listen to audiobooks along the way or when spending time in the tent such as on the mountains. However, when you exercise a lot all day, often experiencing physical discomfort (heat, hunger, fatigue, cold, etc.), then spend additional physical energy on basic necessities such as food and shelter, you simply don’t have much mental energy left at the end of the day. What I had left was often consumed by organizing the upcoming transport or expedition logistics or dealing with unexpected issues such as bike repairs.

After coming home from my big adventure I had the time over the last couple of months to immerse myself in education and entertainment. A bit of context here: My wife and I have a lot of electronic gadgets at home. We have a half dozen digital cameras, mostly small and versatile waterproof point-&-click’s for the road (Panasonic, Olympus), as well as our semi-professional Nikon D300S. 2 Flip Mino HD video-recorders and one somewhat older Sony Camcorder. Several TV monitors, including 2 more modern flat-screen models (Samsung, Sony). After buying an early Toshiba HD DVD player we needed to switch to a Samsung Blu-Ray player. We have each one of the 3 generations of Amazon Kindle book readers. There are several Bose entertainment systems, noise cancellation headphones as well as iPod docking units throughout our home and offices. Last I counted we had a total of 5 Apple iPhones and 4 iPods. I’m not counting the replaced RIM BlackBerries anymore. In September 2010 we bought our first Apple iPad, soon to be followed by another one – just waiting for the second generation model. We also tend to buy some more of these as gifts for our extended family, thus contributing our share to the economic recovery in the US. A few companies do get a lot of repeat business from us, certainly including Apple and Bose.

We enjoy watching a NetFlix movie every now and then, both streaming as well as traditional DVDs which come in the mail. This holiday season saw the addition of a Nintendo Wii game system, and we likely will upgrade my son’s Dell Windows PC shortly. To keep up with bandwidth performance, we recently upgraded to a new Motorola cable modem and Cisco wireless router. As you can see, no shortage of gadgets on the home entertainment front.

The inexorable digitization of content – ebooks, photos, movies, news, audiobooks, ecourses, podcasts – has a lot of promise. But it also requires new approaches to managing your own libraries. For example, my wife spent years building a fairly large personal audio-collection including more than 600 purchased CDs, importing and rating more than 7000 songs in iTunes. She likes to manage our NetFlix queue with the iPad app. We mutually share our ebook library of ~100 titles and manage it using the myKindle website. I accumulated a growing collection of several dozen audiobooks on iTunes, mostly during the time I commuted to work and discovered the in-car iPod delivery of audiobook content as very useful. We manage our tens of thousands of digital photos on the Apple iMac, using first iPhoto, then Aperture as powerful editing and management software. It now takes longer to import and tag the photos than to shoot them in the first place! We share many of those photos using Apple’s Mobile Me gallery as well as Google‘s Picasa. Oh, and let’s not forget the backup using Apple’s Time machine…

The convergence and on-demand availability of content enables new experiences. One recent purchase brought this to a new level: We bought the little Apple TV device. The little box was installed and connected to our TV in minutes. The small remote control is very simple to use and the online menus are very intuitive. It sure is nice to be able to search and instantly view movies from various sources now (iTunes, NetFlix, YouTube). Or stream one of the hundreds of music channels. But the real kicker is the seamless integration with our own libraries of music (iTunes) and photos (iPhoto/Aperture/MobileMe). Since we have so much content on those libraries already, it works great for us. We could do similar things before, by attaching an iPod or a camcorder to our TV. Now, thanks to the fast wireless network connectivity (802.11 n), we have access to all our personal music and photos at our (remote control’s) fingertips, from the comfort of our couch, without having to deal with computer keyboards or additional cables. When you see that slide-show of your last vacation, with your favorite playlist in the background, in between a short news podcast and that new NetFlix movie all from your little remote control, it really is a new experience of home entertainment!

Now this is certainly not the last word in convergence for home entertainment, and at the annual Consumer Electronics Show in Las Vegas (which starts today) we’ll likely see a lot of new offerings towards Smart TVs. And while the proprietary Apple system is not for everyone, the low incremental price point ($99) made Apple TV a no-brainer for us. It will be a while before we can bring that kind of entertainment with us on the road…

January 5th, 2011

No adventure can be reduced to a mere set of numbers. The experiences of a year in the outdoors, the endless variety of scenery and people I encountered defies a purely numerical description. That said, I kept a spread-sheet with daily information about distances, times, elevation, accommodation etc. It is fun and interesting to look at some aggregate charts and get some trends and insights from those thousands of data points.

My trip began with the flight to Mount Logan in Canada in May 2009 and ended with the climb of Chimborazo in Ecuador in June 2010 after a total of 415 days or about 14 months. There were several interim ‘vacations’ during this time to reconnect with my family. For example, I flew back home from Mexico and from Argentina for 1-2 weeks of rest, as well as from Panama at the midpoint of the journey for Christmas and New Years. I also spent a lot of time with travel by plane, bus, ferry, train or rental car. Much of this was caused by the logistics to align all the mountains on time as well as the decision to ride South-America from the bottom-up to take advantage of the Southern summer. When I was not on vacation or in transit, I spent my days either riding, climbing or resting as follows:

Ride: 185 days (45%)

Climb: 78 days (19%)

Rest: 46 days (11%)

Vacation: 66 days (16%)

Travel: 40 days (9%)

Total: 415 days (100%)

Here is a break-down of the 263 days spent either cycling or climbing by country:

Number of days spent climbing or cycling by country

This shows the long time spent in Argentina and all the large countries of North-America. There were 4 expedition-stye mountains with 10 days or more: Huascaran (Peru, 10d), Aconcagua (Argentina, 13d), Denali (Alaska, 15d), Logan (Canada, 16d). I chose to spend much more time riding in Argentina as compared to Chile due to the rainy weather in South-Chile and the hostile Atacama desert in the Northern part of Chile. The smaller Central-American countries took less time, as expected. In Peru I started to take bus transfer to reduce the distance, and in Ecuador I only rode 1 day for the same reason. I skipped Colombia for reasons explained before on this Blog.

How far did I ride each day? Looking at the cycling portion, the total distance is as follows:

North-America: 10850 km (54%)

Central-America: 2916 km (15%)

South-America: 6297 km (31%)

Total: 20063 km (100%)

Here is a break-down of the average daily distance by country:

Average distance (in km) per day by country, grouped by continent

A couple of comments (Ecuador is excluded since I only rode 1 day there):

Average distances riding in South America were shorter than in North-America. The main factors were the rough terrain (Andes), weather (rain), and longer daylight hours in North-America.

Chile stands out as the toughest country. Riding in the cold rain of South Chile is no fun, and getting started again after a rest is even worse, so I often called it a day after just 3 or 4 hours. And I didn’t even attempt the more extreme routes with multiple Andes crossings and rougher gravel roads!

Canada saw the longest rides. The weather was excellent and the long daylight hours allowed me to ride, rest, and ride some more until very late at night. The terrain is also sparsely populated, and in order to get a great meal at a restaurant I usually tried to reach the next village – resulting in many long days of cycling.

How often did I sleep in my tent? Before my departure I described my approach as follows: I prefer to sleep in the tent if the weather is good and if the place is safe. I started the ride in Prudhoe Bay, Alaska on July 1st. Guess how many times I slept in my tent in July? Answer: 31 times! The (Northern) summer 2009 was just great, with very little rain and lots of sunshine and sheer endless hours of daylight. Who would not want to spend time outside and stay in the tent? Besides, the inside netting kept the mosquitoes at bay, a distinct advantage over many a sticky hostel room. Here is how my nights stacked up tent vs. hostel vs. other (at a friend, in a plane or bus, a police or fire station, etc.):

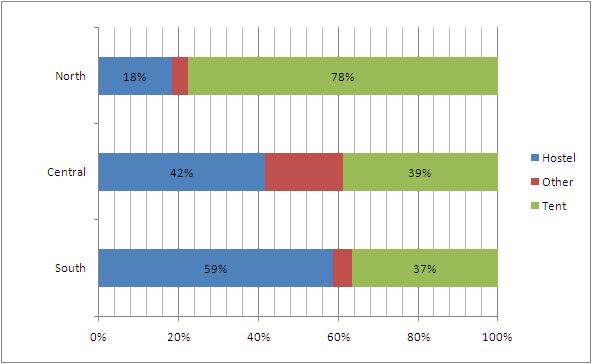

Type of accommodation (tent vs. hostel) by country

Again a few comments:

The nights in Alaska and Canada were almost entirely spent in the tent, during the expeditions on the mountains for obvious reasons, and on the road mostly due to the sunny summer weather. The only times I stayed in a hostel were in Whitehorse and Anchorage just before departing for and when returning from the mountain expeditions. This way I could leave my bike and other gear at those hostels as well.

Argentina and Mexico were a mixed bag; while mostly dry and sunny, there were many stays in cities without camping facilities, so pitching the tent just would not have been safe.

In most of the other South- and Central-American countries I was more often staying in hostels. For one, they are cheap and fairly safe, especially compared to the tent on the soccer field in town. The majority of the tent nights in places like Peru, Chile and Bolivia came from the mountain climbs.

About half of the countries saw 10 nights or less. Even with the time required to climb the mountains, in Central America it is a good rule of thumb to assume that you’ll be in a new country every week!

Frequency of accommodation (tent vs. hostel) by continent

The same data displayed in relative terms reveals the different situations by continent. The tent-to-room ratio can be summarized as follows:

In North-America the tent nights outnumbered the hostels about 4 : 1.

In Central-America, it’s about 1 : 1. Here I was more often staying at some unusual place, for example a fire or police station, a private home invited by a friendly local or a hut in the mountains.

In South-America, the ratio was almost 1 : 2. Again, bad weather, cheap prices and better safety made hostel rooms win out over pitching the tent.

There are many more aspects and averages one can draw from this data-set. For example, my overall daily average on the bike was this:

Time: 6 hrs

Speed: 18 km/h

Distance: 108 km

In terms of elevation gain on the bike, there were big differences by country and region. The Dalton Highway in Alaska is a roller-coaster with up to 2000 m vertical per 100 km. Similarly Mexico had more mountain passes than I had expected. On the other hand, there were very flat days in the Baja California or in the pampas of Argentina with less than 50 m per 100 km. Even without big mountains, many small hills do add up as well. Overall, I had about 800 m elevation gain per 100 km, resulting in about 165,000 m vertical gain over the entire trip. That’s more than 18 times by bike from sea-level to Mount Everest! Since riding uphill is one of the least comfortable things on the recumbent bike, and carrying/towing a lot of weight makes even a slight uphill into a serious challenge, I often tried to avoid big hills when choosing between alternate routes. For example in Costa Rica, I didn’t follow the Panamerican Highway, as it leads through the capital San Jose (bad) and over at least two 3000+ m passes (very bad). Aptly, one of those is called ‘Paso de la Muerte’ and features the highest point of the Panamerican Highway at over 3400 m ASL! Instead I stayed near the Pacific Coast, as do most of the long-distance cyclists. After all, who wants to take a chance when you can avoid the pass of death!

November 12th, 2010

It’s my son’s birthday today and he is turning 13 – ah, those teenage years ahead! When I drove him to school this morning he was obsessively checking his email and text messages on his new iPhone. He bragged about how many Birthday related texts he was getting on Facebook and thus how ‘popular’ he is. “So how many ‘friends’ do you have on Facebook?” I asked. “About 500.” I raised my eyebrows. “And Sarvenaz (his 20-year old sister) has over one thousand!” he adds to my astonishment.

1000 friends? I may barely remember 1000 faces, and I certainly could not even remember all their names, or have a meaningful relationship, much less a true friendship with that many people. Inflationary times for the friendship currency? The number goes up; the value goes down? Certainly some people are far better than me at remembering names or details about the social life of others. But what does the notion of ‘friend’ mean when it comes by the thousands?

I remember Dunbar’s number of about 150, named after anthropologist Robin Dunbar. According to Wikipedia, this number “is a theoretical cognitive limit to the number of people with whom one can maintain stable social relationships. These are relationships in which an individual knows who each person is, and how each person relates to every other person”. On my LinkedIn network I used to only accept invitations from people I knew well enough that I could make meaningful statements about them, say to a headhunter who was checking a reference. And indeed my number of 1st degree connections – a better term than ‘friend’ – is currently 154. The average number of their connections is also similar to that (159), thus spanning a number of around 25,000 2nd degree connections. That’s a lot of people you could get introduced to by a mutually well-known person. And for the purposes of finding a job (as I am trying to do now) or experts in certain areas, this is very helpful.

While Dunbar’s number limits the number of strong ties, thanks to social networks we now have the tools to maintain much larger networks of weak ties. And as sociologist Mark Granovetter has pointed out in his influential paper ‘The Strength of Weak Ties‘, in marketing or politics, weak ties enable reaching populations and audiences that are not accessible via strong ties. We stand a good chance of finding the next job via an unexpected source, a person who knows other people and companies neither we nor our strong ties know, hence the strength of those weak ties.

It is interesting how many people seem to appreciate maximizing the number of their Facebook friends, LinkedIn connections, and Twitter followers. People love getting attention, and the size of their network seems to boost the size of their ego. While it is true that someone with a million followers will be heard more than someone with a hundred, a big following is not the same as big influence. In a rigorous analysis of Twitter data, authors from the HP Social Computing lab point out that popularity is not the same as influence. To quote from the conclusion of their paper on ‘Influence and Passivity‘ paper: “This study shows that the correlation between popularity and influence is weaker than it might be expected. This is a reflection of the fact that for information to propagate in a network, individuals need to forward it to the other members, thus having to actively engage rather than passively read it and cease to act on it. Moreover, since our measure of influence is not specific to Twitter it is applicable to many other social networks. This opens the possibility of discovering influential individuals within a network which can on average have a further reach than others in the same medium, regardless of their popularity.”

Networks are certainly valuable for each of us individually. Likewise, a network’s value increases with its size. Hence a social networking company’s valuation correlates with the number of members. I thought it was interesting that analysts have put an average value of $50 per member – hence the astronomical valuation of Facebook with 500+ million members leading to $25+ billion. I don’t know how this number is arrived at. When I think back to my bike trip through the Americas, seeing those predominantly young and poor kids in Central- and South-America updating their Facebook accounts at Internet kiosks, assigning a monetary value of US$50 to their free membership seems optimistic, to say the least. I can’t help but thinking that some of these valuations will undergo a ‘correction’ just like many of the hyped business models of the dot.com era came down for a hard landing around 10 years ago.

Lastly, dealing with average value in large number of connections is complex and often surprising. In their excellent book ‘Making Great Decisions‘, the authors Henderson and Hooper give us something to think about: If your business has, say, 100 customers, then statistically 80% of your profits come from just 20% of those customers. So numerically, each one of the ‘good’ customers is on average 16 times as valuable to you as any of the ‘other’ customers. (1/4 of the number bring in 4x profits, that’s 16x profit per customer). I suspect the same is true with regards to influence and value in social networks as well. As with customers, so it is with friends: It’s important to know who the ‘good’ ones are, because they matter so much more.

If business contacts are about making money, social contacts are about making a difference. Which brings me back to family and close friends. Regardless of the size of our own social network, we will always have a much smaller number of strong ties, and those we value disproportionately because they make a big difference in our life just as we do in theirs!

November 5th, 2010

Since coming home after finishing my project in Ecuador I have been reviewing all my photos and scanning through my emails and daily notes I took while on the road and on the mountains. Now that I have begun writing the book about my adventure, I realize the need to immerse myself back into the details of certain situations to regain that same perspective of being ‘out there’ as compared to sitting back home and writing from a distance.

I have also been reading several books in the last two months, mostly about happiness and behavioral economics. It fascinates me to understand what incentives we respond to, what influences our decisions and causes us to make mistakes and/or irrational decisions, and what we think will make us happy. I have mused here before on the topic of enjoyment and happiness, mostly focusing on the difference of short-term pleasure (instant gratification) by satisfying simple urges vs. long-lasting happiness after achieving complex goals.

When reviewing my materials I am often struck by how I described the experience back then as compared to how I remember it now. For example, there is much more fatigue and discomfort in those daily notes and emails than what I remember most from certain parts of my trip. It has been known that our long-term memory of experiences can differ substantially from the actual sensory experience at the time, specifically when it comes to the sense of happiness. Cognitive psychologists have studied this experimentally. A typical experimental setting would have volunteering subjects carrying a pager throughout the day; they were asked to record their level of happiness each time when the pager beeped at random intervals. Later they were asked to rate their overall level of happiness when thinking about their lives over the entire period of time. The first is a rating of happiness in the present moment by the experiencing self; the second is a rating of happiness about the past by the remembering self. As Daniel Hahneman has pointed out, there is often a big difference between the experiencing and the remembering self.

If I had been paged at random times throughout my trip, chances are you would find a lot of low happiness recordings: Being tired and thirsty on the road while cycling towards my daily goal; being cold and hungry on the mountain while climbing towards the next camp. Yet, when asked after the fact, my recollection is far more joyous and optimistic – I am genuinely happy about the entire experience. Why is that?

I suspect that there are at least two reasons:

First, the way our memories work at the neurological level is such that we remember emotionally intense situations more clearly than the average, dull moments. The joy of reaching the daily goal or camp, taking that hot shower and eating that satisfying meal is remembered long after the many hours riding towards the horizon on seemingly endless roads will be forgotten. The exciting sight of a grizzly or black bear in Canada is remembered more vividly than the endless tundra or forests during what someone called “counting 3000 miles of trees”. While we forget the multitude of average moments feeling rather tired and uncomfortable, we remember the few exciting moments feeling exhilarated very well.

Second, memories and biases therein are self-reinforcing when recalled frequently. The experiencing self is gone forever shortly after the event; thereafter it is only the remembering self controlling the ‘experience’. And if one favors one emotion over another for whatever reason one tends to remember and associate that emotion more with the actual event even if it wasn’t as strong when it actually happened. If I repeatedly state that I generally felt great while up on the mountain, I will over time be less able to distinguish that stated sentiment from how I really felt up there anticipating getting out of the sleeping bag in the morning into -25 degrees freezing air. Not until I look at my daily notes typed on the iPhone for that day…

The remembering self tells us how happy we (think we) were in the past, the experiencing self tells us how happy we are in the present. One could add the predicting self which tells us how happy we (think we) will be in the future; it obviously plays a huge role when we are planning our journeys or adventures. However, as psychologists like Daniel Gilbert or Dan Ariely have found out, we are notoriously poor predictors of how certain events will impact us emotionally. We predict being deliriously happy after winning the lottery or devastated after a crippling accident. Yet, a few months after such events most people are right back to the level of happiness they had before. So did I fool myself predicting that this adventure would make me happier? Something to analyze in more detail in my book…

October 20th, 2010

Megler-Astoria Bridge over the mighty Columbia River, connecting Washington State and Oregon State near Astoria

In going through my photos I realized I had cycled across hundreds of bridges along the Panamerican Highway. Some small and seemingly insignificant, some majestic and famous. All of them helping to make the journey easier and often offering great vistas. I published a commented selection of 20 bridges on Picasa. These range from bridges across mighty rivers like the Yukon or Columbia River to the Golden Gate bridge over the bay of San Francisco to the Puente de las Americas across the Panama Canal. It also includes a few smaller but scenic bridges in South-America, such as on the Carreterra Austral in Chile.

Bridges have always been a symbol of connecting two opposite shores, of enabling the seamless continuation of a journey. Some of these bridges are icons of engineering feats, of daring solutions to a natural challenge or gap. Many invited to stop and pause, take in the view from up there and reflect about the ingenious design and hard mechanical labor that went into building them.

Longest bridge on the Alaska Highway near Teslin, Yukon.

Most of these bridges like the Nitsulin-Bay-Bridge on the Alaska Highway didn’t exist in the early 20th Century; back then one would have had to take a boat to get across the water. Of course I still had to make some such crossings, such as the ferry from the Baja California to mainland Mexico, the mini-boats across Lake Titicaca in Bolivia, or the ferry across the windy Magellan Straight separating Tierra del Fuego from the Northern part of Patagonia. (And I got stuck once for two days when a scheduled ferry ride was cancelled near Villa O’Higgins in South Chile.) I always enjoyed riding across bridges. Often it reminded me of the many things we take for granted in this day and age.

Reaching the Golden Gate Bridge on sunny Labor Day in September 2009 was certainly a highlight of my trip. I had seen a photo of this same bike on the website of Stefan Dudli who rode the Panamerican Highway on this recumbent the previous year. Picturing this moment was one powerful visual motivator for me during the initial part of my journey.

Puente de las Americas over the Panama Canal

Reaching and crossing the Bridge of the Americas over the Panama Canal in December 2009 was a very emotional moment for me. Long days of intense heat and many miles had finally come to an end with reaching this bridge with the elegant arch on the outskirts of Panama City. I realized I had finished the North- and Central-America part of my journey and would soon be reunited with my family for a well-deserved break over Christmas and New Year. Riding up the bridge span was exhausting and with the narrow lanes and lots of traffic a bit dangerous. But rolling down the other side brought elation and relief from all the tension. Tears of joy rolled down my cheeks – I will always remember that great feeling of accomplishment.

“Let’s cross that bridge when we get there!” This saying also embodies the sentiment that many things along a trip like this can’t be planned in detail and have to be dealt with in a somewhat ad-hoc fashion. You never quite know what the next day is going to bring, what little challenges are thrown your way, what actual or metaphorical rivers need to be crossed. Accepting that fact, improvising at times and going with the flow of things made the trip less stressful and more fun.

I noticed sponsorship signs of Japanese companies on newly built bridges in Nicaragua, wondering about the intricate network of global interests and dependencies. I also read about individuals who are building bridges as aid to develop poor countries. Says Harmon Parker in this recent article on bridge projects in rural Kenya:

“I have built many bridges in very remote areas for the ‘few and the needy’ that a larger organization may not consider,” he said. “Knowing this bridge will probably save at least one life is what makes me tick. … I build bridges because I want to save lives, lives that I will never know about.”

Whatever the motivation, we owe tribute to those who came before and built the bridges. They serve as a classic and enduring testament to the ingenuity and willpower of mankind. By streamlining the journey to discover a land such as the Americas they also empower our inner journey to discover ourselves.

September 22nd, 2010

Next Posts

Previous Posts